The Wily Morel

The Wily Morel

Slowly comprehending my unbridled arrogance, hot tears stung my eyes. Hiking alone for hours in California’s towering El Dorado National Forest, my gaze cast downward onto endless forest floor, I lost my way. Rather than following a path or trail, or cleaving closely to the road, I thoughtlessly meandered an enormous length of woods searching for one of springtime’s great culinary gifts: Morchella, the true morel mushroom. Detaching from my mushroom eyes, I looked up and realized, with a gut-wrenching bolt of panic, I had absolutely no idea where I was. And thanks to my helter-skelter approach to foraging, I had no idea from which direction I had come.

Complete damn amateur.

And the day had begun so well. I’d taken explicit driving directions from my foraging guide the day prior. We’d spent the day together hiking through several forests, 5,000 feet up the mountain, a 20-mile drive from its base. Not another soul in sight, I gratefully thought at the time. While we didn’t score the mother lode of fungi fantasies, my constant travel mate, a heavily patined carbon steel knife, cut through the stems of a half-dozen large morels, enough for a good supper. Convinced that my highly focused, solo return the following day would yield far better results, I was already anticipating packing the dehydrator; its reassuring whirring noise filling the kitchen with the funky, earthy aromas of mushroom, while glass Mason jars crammed with dried bounty filled the pantry.

Excitedly I rose with the sun, greeting the day with a cup of tea, a stretch and an early toke on the balcony of my lodging, overlooking newly green vineyards lining the bosomy hills of the town Fairplay. I loaded a compass and altitude gauge onto my phone and filled a water bottle. Crackers, cheese, and foraging knives went into mesh bags and a wicker foraging basket, which have ample openings for the morel mushroom’s thousands of microscopic spores to fall to the ground, the wind reseeding their natural habitat for the years ahead. As explained by mushroom guru Dr. Thomas Volk from the Department of Biology, University of Wisconsin–La Crosse, a morel mushroom is actually the vessel the Morchella species uses to produce and disseminate their spores. Morel hunters will brag of witnessing morels ‘smoking’ as they release their millions of spores. Most mushroom gills are designed to allow wind to spread their seed aerodynamically. Not so for the morel. Morels produce thousands of ascospores (spores inside cells) encased within its webbed tissue. These spores are driven out to sow when this tissue dries and shrinks. This disadvantaged design was not evolution at work but instead created by a strain of yeast.

Even after they’re released, it’s rare the ascospores cross-pollinate. And if they’re fortunate enough to be shepherded to germination by Mother Nature, it can be years of gathering nutrients and waiting for the convergence of ideal conditions (soil, temperature, moisture); the perfect fungal storm. Mycelium, the mushroom’s vegetative root, is composed of long, branching cells called hyphae, which ground and feed the mushroom. These roots also produce sclerotia, a hardened mass of mycelium that’s used as backup when environmental conditions threaten the fungi’s existence. It’s the sclerotia that produce the mushroom’s fruiting body.

Lest it be forgotten, the mushroom is the fruit of a mold.

And because of this aberrant little fact, morels are not actually considered mushrooms in the true sense of mushroom taxonomy. Truffles share this same trait with morels, both hailing from an entirely different class known as Ascomycetes.

I stealthily slipped out the hotel’s front door, escaping the creepy hospitality of the property manager. Driving the back roads of the conifer-covered central Sierra Nevada Mountains, I wound past the Bluebird Haven Iris Gardens, its hills ablaze in late spring resplendence; past Glory Hole Road; past thousands of tiny, canary-yellow flowers blanketing an entire valley; past dozens of swallows playing in the early morning sunlight, their nests built under an ornately arched bridge reflected in a crystalline stream.

An hour later, my old German tank, its diesel-fired engine huffing and puffing, was slowly making its way up the dramatic Mormon Emigrant Trail. Tucked into the El Dorado National Forest, this 170-mile trail was cleared in 30 days by The Mormon Battalion, who had spent the winter of 1847 in Northern California at the command of their leader, Brigham Young. To return home to their church and families, they literally blazed their own trail, which was put to further use soon after by those seeking more earthly fortunes in California’s Gold Rush.

As soon as the altimeter read 4,000 feet, I slowly drove the paved, desolate road, canvassing for parcels of woods charred black from the California Forestry’s moderate-intensity, controlled burns; ideal habitat for the morel. ‘Stay in the burn’ was the mantra repeated many times by yesterday’s foraging guide. While morels grow outside of burn zones, fungi lovers have long believed those that sprout near a fire’s one-year-old char are more intensely flavored. The theory is the delicious combination of dying trees, here the conifer, and the extermination by burning of forest floor creates a veritable feast of decayed organic matter for the morel. Fire also eliminates the insects that feast upon them, allowing humans to gorge on bug and slug-free mushrooms.

Genetic analysis done by scientists at Oregon State University found that morels have grown for at least 129 million years, splitting off from other fungus at the dawn of the Cretaceous Period, when they were found underfoot of dinosaurs. And while there are more than 150 related species, the morel has remained mostly unchanged and true to its roots, right down to its mycelium. Morels are saprotrophs, feeding off dead or dying trees and decomposing leaves, returning nutrients to the soil. More unusually, morels are also mycorrhizal fungi, which means that while they feed off the tree, they also provide it with water and nutrients. Nature’s interdependence, inclusive of the tiniest organisms, is mind-blowing.

Fully replaced each year, the morel’s mycelium doesn’t grow back, so it can be harvested right at the base. But while most mushroom caps are shaped to allow rain to wash away forest dirt and detritus, the morel’s honeycomb design easily traps debris, demanding the stem be cut carefully and cleanly, just above the soil. And to further their arduous harvesting, morels break easily, lacking the tough skin and fibrous stem found on other mushrooms.

One pound of premium, dried morels commands upwards of $300, and is comprised of roughly ten pounds of laboriously foraged fresh morels. With extremely limited success farming morels commercially, the season is dictated by nature and by the number of eyes foraging the wilds for the elusive fungi. Referred to as Hickory Chicken or Dryland Fish or even Molly Moocher, the highly prized morel’s nutty, dark flavors of earth and woodland compels ardent springtime foragers around the world into their countryside, and then to the family stove.

As trees begin to bud and snow melts away, unfiltered sunlight warms the ground and the spring wildflowers bloom. It’s then the morel mushroom slowly emerges, a reticent background singer now thrust to center stage on the forest floor. The mushroom can take several weeks to achieve full size, living for two weeks before decomposing. Their foraging season often continues for several months, the higher elevations the last to be seduced by spring’s warmth.

Like high stakes gamblers studying odds and players, commercial morel pickers are sure to familiarize themselves with forest fires and weather patterns. Fires in the summer prior to spring’s harvest provide an ideal environment for the morel mushroom’s germination. Add a heavy winter snowpack and a wet, early spring and one can harvest 75–100 pounds of morels per day.

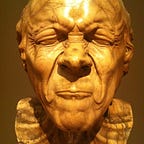

Morels are ugly but quite distinct; one of the many reasons I wandered the forest unguided and alone in search of them. I couldn’t possibly mistake the morel’s easily recognizable, honeycomb design for any other liver-melting species of mushroom. Even the toxic false morel’s appearance is obviously different. One to six inches tall and sponge-like, the morel can be found pushing up through the leaf litter. Like a tiny brown Christmas tree, the morel’s cap is cone shaped and roundish around the middle. Many times I’m giddy, convinced I’ve hit literal pay dirt, only to find small pine cones at my feet. The morel’s stem and cap are hollow, with the stem firmly attached to its base. It sounds clear and hollow when tapped, like a felt winter hat.

Hunting and fishing and foraging for food or artifacts provoke in me a greedy high akin to gambling; if I just get out there earlier and stay out a bit longer, try many different spots, stay in the game, get in the zone, I’m bound to get lucky. But I wasn’t feeling too lucky having gone astray for hours and hours in fathomless forest. Numerous large animal tracks in the mud had me looking over my shoulder in each clearing through which I passed. As the sun moved westward, I envisioned sleeping in a pile of leaves, maybe even winning The Darwin Award, but I prayed, not posthumously. I climbed a steep hill thick with pine, hoping to get a better look from above, my mind racing, ticking away with recriminations, self-loathing, panic. I tried to steady myself by reciting a list of morels’ habits and habitats:

Their preferred soils contain lime and calcium with a loamy mix of decaying organic matter, sand and clay.

Morels appear after the first rains of spring and after the nights warm to more than 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

Morels can be found in old logging areas and forests with downed or burned trees and in areas where water once stood, near rivers and floodplains.

The name ‘morel’ comes from the German word ‘morchel’ meaning mushroom.

As I neared the hilltop, my thoughts turned to calm gratitude for the forest’s fragrance, for the dappled sunlight, for a glimpse of a hawk and an owl, for the very large hunting knife in my basket. Descending the opposite side of the hill, I could only think of dinner.

After many hours and the third logging road hiked, I gratefully caught the glint of my wagon in the twilight of early evening. I sat on the ground next to the car, unlaced the hunting boots from my battered feet and wept, overjoyed at not spending the night alone in the deep woods. Demoralized, but not demorelized, my mushroom basket was heavy with morels.

The land was rinsed from a dozen black morel mushrooms. The chopped stalks of red Tropea onions, liberated days earlier from the garden, were sautéed with a generous corner from a block of salted Sonoma butter. The mushrooms were cut lengthwise, inspected for critters and rinsed before being fanned over the wilted onions to cook through. A healthful splash of Bartoli Marsala sent up a steamy cloud aromatic of sunny, briny Sicily. Several eggs, fancy in their blue-green shells, were whipped with heavy cream, sea salt and a course grind of black and white pepper. Over a low flame, the eggs were married to the mushrooms, shirred with a whisk until just barely cooked, and finished with a spoon of fresh sheep’s milk ricotta. Pouring glasses from a hoarded bottle of Littorai Chardonnay, now fawn-colored in its advanced age, I recalled a warning read from one of the mycology books lining my desk: eating morels while drinking alcohol may produce symptoms of great intoxication.

Morels: California’s other cash crop.